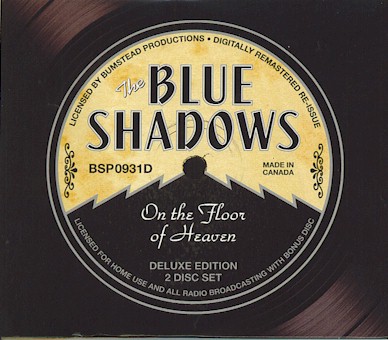

Front cover

|

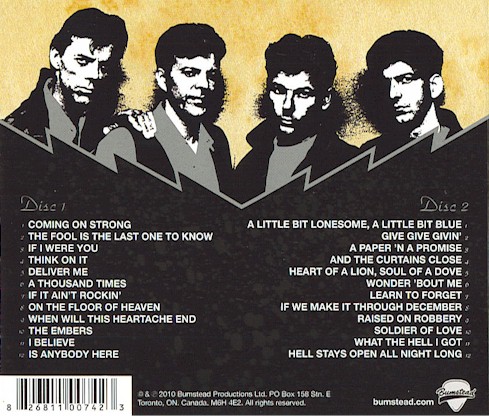

Back cover

|

Inside Left

|

Inside Center

|

Inside Right

|

Back Flap

|

|

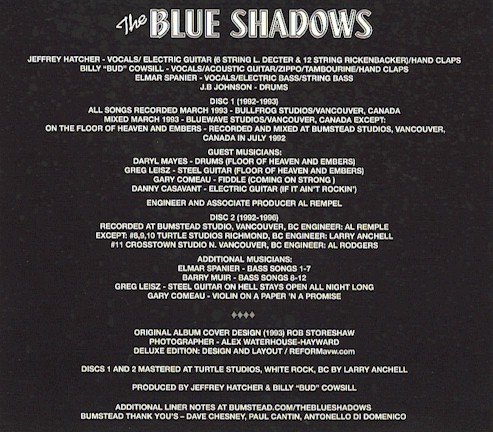

The Blue Shadows

JEFFREY HATCHER - VOCALS/ ELECTRIC GUITAR (6 STRING L. DECTER & 12 STRING RICKENBACKER)/HAND CLAPS

BILLY "BUD" COWSILL - VOCALS/ACOUSTIC GUITAR/ZIPPO/TAMBOURINE/HAND CLAPS

ELMAR SPANIER - VOCALS/ELECTRIC BASS/STRING BASS

J.B JOHNSON - DRUMS

DISC1 (1992-1993) ALL SONGS RECORDED MARCH 1993 - BULLFROG STUDIOS/VANCOUVER, CANADA

MIXED MARCH 1993 - BLUEWAVE STUDIOS/VANCOUVER, CANADA EXCEPT:

ON THE FLOOR OF HEAVEN AND EMBERS - RECORDED AND MIXED AT BUMSTEAD STUDIOS, VANCOUVER,

CANADA IN JULY 1992

GUEST MUSICIANS:

DARYL MAYES - DRUMS (FLOOR OF HEAVEN AND EMBERS)

GREG LEISZ - STEEL GUITAR (FLOOR OF HEAVEN AND EMBERS)

GARY COMEAU - FIDDLE (COMING ON STRONG )

DANNY CASAVANT - ELECTRIC GUITAR (IF IT AIN'T ROCKIN')

ENGINEER AND ASSOCIATE PRODUCER AL REMPEL

DISC 2 (1992-1996)

RECORDED AT BUMSTEAD STUDIO, VANCOUVER, BC ENGINEER: AL REMPLE

EXCEPT: #8,9,10 TURTLE STUDIOS RICHMOND, BC ENGINEER: LARRY ANCHELL

#11 CROSSTOWN STUDIO N. VANCOUVER, BC ENGINEER: AL RODGERS

ADDITIONAL MUSICIANS: ELMAR SPANIER - BASS SONGS 1-7

BARRY MUIR - BASS SONGS 8-12

GREG LEISZ - STEEL GUITAR ON HELL STAYS OPEN ALL NIGHT LONG

GARY COMEAU - VIOLIN ON A PAPER 'N A PROMISE

ORIGINAL ALBUM COVER DESIGN (1993) ROB STORESHAW

PHOTOGRAPHER - ALEX WATERHOUSE-HAYWARD

DELUXE EDITION: DESIGN AND LAYOUT / REFORMavw.com

DISCS 1 AND 2 MASTERED AT TURTLE STUDIOS, WHITE ROCK, BC BY LARRY ANCHELL

PRODUCED BY JEFFREY HATCHER & BILLY "BUD" COWSILL

ADDITIONAL LINER NOTES AT BUMSTEAD.COM/THEBLUESHADOWS

BUMSTEAD THANK YOU'S - DAVE CHESNEY, PAUL CANTIN, ANTONELLO DI DOMENICO

|

|

Liner Notes

In the late ‘60s, popular music came to a crossroads. One sign read “rock”, the other “country”. And popular music headed off in either direction, rarely to meet again.

Billy Cowsill started off down the rock and roll trail, achieving fame and fortune as a teenage warbler with the family band, the Cowsills. (Remember “Hair” and “The Rain, The Park and Other Things”?) But being a teenage idol in “Americas’s First Family of Music” soon lost its allure, and Billy left the family nest at the height of their success.

To paraphrase Neil Young, Billy left the middle of the road and headed for the ditch; in his words, “getting my ass kicked left and right, spittin’ in the devil’s eye and watchin’ it sizzle”. Cowsill had a vision of forging the honest emotion of stone--cold country with passion and energy of rock and roll. The vision took him to L.A where he studied production with Harry Nilsson to Oklahoma where he played with J.J. Cale, to Lubbock where he hung out with Joe Ely. He opened a bar in Austin with the last of his Cowsills cash, and “drank it dry”.

Eventually, he wound up in Vancouver. There, he ran across standup bassist Elmar Spanier, a snappy dresser who could sing harmony, play his monstrous instrument like he was ringing a bell and was blessed with supernatural ability to score gigs.

They joined forces and set about conquering the world. But it proved to be a long, hard struggle. On any given night, Cowsill and Spanier could be devastating, reeling off spellbinding renditions of classics by Hank Williams and Roy Orbison alongside snazzy originals like “Embers”. But Western Canada is no Nashville, and the duo found themselves plying their trade to a small, but devoted cult following.

By day, they demoed their originals. By night they played in bars. Some excellent musicians came and went in their group, but drummer J.B Johnson came and stayed. J.B. had the beat, he had the feel, and he had the look--a neo--George Jones brushcut.

Enter Jeff Hatcher. As singer, songwriter, and guitarist for a number of fiery bands in Winnipeg and Toronto--the Fuse, the Six, the Big Beat-- Hatcher was well know across Canada amongst connoisseurs of ‘60s pop/rock.

Something happened when Hatcher signed on as guitarist-- something magical. The quartet now know as the Blue Shadows headed back to the aforementioned fork in the road and found a lost highway, a place where country rocks and rock twangs.

Hatcher’s touch on the guitar fit in perfectly with Spanier and Johnson’s subtle way of delivering a tune. But it was the vocal harmonies between Hatcher and Cowsill that really took the audiences breath away.

When Billy and Jeff harmonize, their voices blend so well you can’t tell who’s singing. Cowsill sings high harmony and Hatcher low, but at certain points they intersect and switch, seemingly unconsciously. Their harmonic camaraderie recalls Don and Phil Everly, Nick Lowe and Dave Edmunds, or John Lennon and Paul McCartney. It’s like they’re twin sons of different mothers.

Angels weep on “The Floor of Heaven” when their voices ripple across the sky. Their sweet, sad harmonies take listeners to a blue side of lonesome on the barroom balled. “Think On IT”. The dramatic Beatlesque harmonies and flourishes of acoustic guitar on “If I Were You” make it sound like a C&W outtake from Beatles ’65.

Strong men break down and cry when Cowsill evokes the spirit if the Big O on “Is Anybody Here”. The big guitar twang and swinging beat of “The Fool is the Last One to Know” sounds like Johnny Cash playing lead for Buck Owens and the Buckaroos. “When Will This Heartache End” may be the best Everly Brothers tune Don and Phil never wrote.

They call their sound “Hank goes to the Cavern Club”. Hank being Hank Williams. The Cavern Club being the Liverpool nightspot where the Beatles began their musical revolution. It’s a sound that is simultaneously fresh and familiar, a sound that uses the past as a springboard to a brave new musical future. And somewhere in the stars, Hank Williams, John Lennon and Gram Parsons are smiling.

-John Mackie – music critic, Vancouver Sun

“In the back room was a radio, an old one, very heavy, the cabinet all wood with silvery cloth covering the speaker. Not a sound came out of it anymore except a low hum. The back part of it had been taken off for some reason so now when the machine was switched on, he could see the tubes in the back warm up and glow a dark blue color. It was best to do this at night because the radio’s tubes would throw shadows on the wall and ceiling. He thought they were mysterious, alive. Blue Shadows. The words even sounded good. A name for something. A train. Or maybe a song.” From “The Circle Time Parade”

by J. Henry

|

|

On The Floor of Heaven Song Notes by Jeffrey Hatcher

Disc 1

“Coming On Strong” – This started with the phrase from Bill that eventually became the title. He also had

the seven-note melody that accompanies the first line of each verse. Like a lot of our tunes which became

duets, when I started to sing the melody and Billy sang the higher harmony, the song suddenly had its

personality and it started “to write itself,” as he and I would come to say of many of the Blue Shadows’

songs.

“The Fool Is The Last One To Know” – Writer, musicologist, and friend Paul Cantin, who notices such

things, jokingly asked me at the time if I was aware of the high prominence the word ‘fool’ had achieved

on our first album. Count ‘em. At the time this song arrived – in about late ’91 or early ’92 – we were just

starting to add original songs to the repertoire. It was the period before the Blue Shadows had their name, a

record company and management team with Larry Wanagas and Dave Chesney, and when I was the new

guitar player and singer in town who had passed the audition. While we played regularly in the local clubs,

Billy was writing with other songwriters, in Calgary, in Vancouver, occasionally heading down to

Tennessee to work with Nashville writers. One time he showed up with this one, co-written with Ralph

Bowden, and we added it to the set. I was getting some feeling about the kind of songs I thought we should

be writing/playing and I clearly recall thinking that I had soon better get moving to assert myself as a writer

for the band.

“If I Were You” – I began to sing some lead vocals early in the band partly because Bill liked the break,

and partly due to his consistent trashing of guitar strings when we played the local clubs. Even when he had

two guitars he regularly broke a string on each. He would announce, “I’ve got two down, boys,” and head

off to the dressing room to put on some new strings. So I started singing some songs. I think I did the lead

vocal to “If I Were You,” though, partly because Bill found the phrasing of the first line of each verse

awkward to sing. This was unheard of for him, and we had a laugh about this auditory hiccup that blocked

his ability to get on top of the line. It’s the first song that Billy and I really wrote together. Again, it was in

the very early days. I was very eager to get a song into the band. I remember we were in the ‘dressing

room’ – really a sitting area at the edge of the staff room - of The Fairview Pub, a club we played regularly.

I showed Bill this new tune I had just started. When I played him the chorus that I had he added the

harmony that immediately ‘made’ the tune for me, and we knew the song was off in the right direction. We

called that effect ‘ringing the bell’ ever after and if a song had that moment in it then we knew we should

keep it.

“Think On It” – This was a song I had played with my brothers Don and Paul in The Big Beat days. At

that time we were rocking and rolling most of the time though this was kind of a Don Williams-inspired

effort. I thought it would suit Billy’s voice. He liked it and – he who could do vocal arrangements even in

his sleep - suggested the vocal parts that the Blue Shadows eventually used. It took the song into what I

thought was an original area of country music for the time.

“Deliver Me” – Another song from my earlier band. Larry had, at that time, located the Bumstead

organization in a set of offices with a recording studio in the back. After Bill and I had learned the song, we

recorded it twice, with each of us singing the lead vocal once. We played it for Larry and Dave in the studio

one afternoon and it was quickly decided that Billy should sing the lead. I was used to it as a faster rock and

roll song. Now it was a mid-tempo country tune that became a very strong live number.

“A Thousand Times” – Another song that Bill brought back from one of his early Nashville trips. We

often played this one as a duo in concert, with just our guitars, in a mini acoustic set in the middle of the

rocking.

“If It Ain't Rockin'” – Again at the Fairview Pub. After the last set one night, packing up while still

onstage, I played Bill the melody and chords for this song I had just started. He liked it right away and told

me, jokingly, “Don’t finish it on your own. I want a piece of that puppy.” The next night I told him I had

finished writing the song that afternoon, though I hadn’t. He sagged almost completely onto the stage floor

and I quickly told him I was joking. We did soon finish it together, writing, as we did many times, in the

Bumstead studio.

“On The Floor Of Heaven” – I had a mental picture of George Jones singing the opening melody to this

song – I had no lyrics yet except the “all men/amen” play on words – and brought it to Bill. We were

playing in Calgary and Bill was staying at musician Tim Leacock’s house. I went over one afternoon to

write. We started and finished the song that afternoon. We were quite proud of it and played it that night

with lyric sheets all over the floor at the base of our microphones. The band liked to perform new songs as

soon as we had learned them. They were always completely ragged and messy the first time, and never

sounded so raw again, but sticking the necks out that way tends to inject adrenaline into a group.

“When Will This Heartache End” – Again, we were in the Bumstead studio. We were taking a break – a

‘break’ meant Bill was smoking and leaning out a window while I was fiddling at the song we were

working on – and to refresh my mind I started on something new. I thought of Ray Charles’ version of “I

Can’t Stop Loving You” and came up with “When will this heartache end” because it has the equivalent

number of syllables. At first I sang it like “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” Billy got excited by it and came back

to sit down. It soon switched into a country tune, became very Everly Brothers-ish, and soon “wrote itself.”

It was a Sunday and the offices were closed except to us with our key. When we were done we found that

somehow we couldn’t get out of the building without setting off the door alarm. We climbed out a window,

jumped onto a dumpster and thus made it down from the second story like the Little Rascals.

“The Embers” – Again in the early days – in about ‘92 - Billy taught me this tune he had written years

before in the 70’s when he was living in Los Angeles. I suggested it could use a middle section. It was very

short and direct as it was, which isn’t necessarily a problem, but I thought this tune needed to “ring the

bell” and reach a crescendo of some kind. A couple of days later we got together at my place and I played

him my idea. Billy suggested a couple of word changes and a new way to sing ‘eternity’ which did ring the

bell. It was finished very quickly.

“I Believe” – One day, while labouring on another song, I took a break. Using a head-clearing technique I

discovered long ago, I just started banging away at the guitar on some chords that became the

accompaniment to “I Believe.” I started singing a melody with no words. I put together the lyrics to the

verses later although I didn’t finish the middle section. I liked the song but thought of it as a bit of a

throwaway – in the best sense - and let it sit while we continued to play and prepare to record. We hadn’t

yet played the song live when it was time to begin recording On The Floor Of Heaven. The day it was time

to do the vocal for “I Believe” I had to make up the bridge in just a couple of minutes because that was all

the time we had, and I had left it until the last minute. Dear Bill, who would happily make jokes about his

memory faculties, once asked me if he had written “I Believe” with me or not because he wasn’t sure.

“Is Anybody Here” – Anyone who tries to sound like Roy Orbison sounds like someone trying to do

something they shouldn’t. No one anywhere could get away with it, and still make it sound original and

dramatic, except Bill. One day, in my head, I heard him singing in the Roy style and I came up with the

first line of the chorus. Billy changed the note of the word ‘song’ from the tonic to the fifth below and “Is

Anybody Here” was on its way to ringing the bell. We finished this one the same day we started it, as I

remember, and were quite pleased at the cute-yet-appropriate sounding verse where Bill sang, “Is this

lonely voice / the only voice” (‘only’ and ‘lonely’ being our wee tribute to Roy O) and me, the guitar

player, singing, “Is my guitar the only one / To strum along?” Many times we braved the line between

quality and cliché, and we had many discussions about how far was too far. Here, I think, is a good

example where we got it right.

Disc 2

The Outtakes

“A Little Bit Lonesome, A Little Bit Blue” - No offence at all intended to the writers of “The Fool Is The

Last One To Know” but I really wanted “Little Bit Lonesome” to be on the first album in place of “The

Fool.” Both songs were hardcore country, which I felt the collection needed, but “Lonesome” was a step in

the direction the Blue Shadows were going and a step away from where Billy’s club band had come. For

those not around in those days, by the way, the band I joined billed themselves onstage as one who played

“only dead guys.” Billy was proud to say, tongue in cheekiness: “We don’t play fat Elvis,” and, if someone

called out a request for a song by a living writer, Bill would say, “Sorry, man, we only do dead guys. As

soon as he’s on the slab we’ll be all over him like a cheap suit.”

“Give Give Givin'” - I brought the turnaround line of “This give, give, giving …” etc. to a writing session

and it became one of the tunes Billy and I completed as something of a songwriting exercise. In this case

we decided to run with the wordplay. We went over the top with this one – the giving and the taking never

quit – but I still kind of like it.

“Paper & A Promise” – Another one that Billy brought back in the early days from a co-writing

adventure. This one seemed to fit the band well both during the “Dead guys” set and the future Blue

Shadows, and we kept it for quite awhile.

“And The Curtains Close” – During the Blue Shadows period I became interested in co-writing with

other writers. Eventually our managers Dave and Larry helped set me up with several of them, among them

Randy Bachman, Barney Bentall and Murray McLauchlan. I also set myself up when I could, with Raylene

Rankin of the Rankins, and Kim Clarke, a Vancouver musician and writer, now in London, ON, with

whom Blue Shadows drummer Jay B. Johnson and bassist Elmar Spanier had played years before (Elmar

actually introduced me to Kim). Kim and I wrote several tunes, and are still in musical touch, and this was

our first one. I dropped a cassette in his mailbox one day with the melody and chords and he gave it back a

few days later with all the lyrics intact. I didn’t change one word, the only time I’ve had that experience.

We demoed the tune, and even performed it live a couple of times, but Billy never was comfortable singing

the subject matter, and we already had me singing lead on a few, so it was put aside.

“Heart of a Lion, Soul of a Dove” – Another from the early days that Bill brought back from a co-writing

session. This one fit very well and we kept it in the repertoire until the end of the band. One of the fun ones

where we switched vocal parts mid-way during the chorus. That is, though Bill sang the melody in the

verses, for the chorus it sounded better that I sing melody and he switch to the upper harmony. This isn’t

usually done, if it’s done at ALL, but we had to because my voice is thin in that upper range whereas Billy

could sing anything anywhere. We often switched off at moments like that and somehow it didn’t sound

incongruous for the lead voice to now sing harmony. One of the odd things about Bill and I singing

together was that our voices were very different – mine more nasal and his the rich crooner’s – but together

we tended to sound like the same person singing twice. We couldn’t figure it and didn’t try; we just

appreciated it.

“Wonder 'Bout Me” – It’s unusual for me to say it but I remember almost nothing about this one. Billy

had a piece of a song from ‘way back and he brought it to an early writing session. I helped a little bit with

the lyrics as I recall. I probably don’t remember it well because I thought at the time it wasn’t going to

make the cut for our live show or for the next recording.

“Learn To Forget” – …and I’ve almost learned to forget this song. A very early writing experience that I

don’t think turned out very well though we did start to get our vocal harmonies more together due to the

writing of tunes like this (and “Heartache” and “If I Were You,” both from the same few weeks period). I

think I started it off and we, again, treated it like an exercise where we had to keep our eyes on the themeprize:

remember, forget, forget, remember, etc.

The Covers

“If We Make It Through December” - Recorded for a 1993 Sony Music Canada Christmas music

sampler entitled Keeping Our Country Christmas Together. Originally released by Merle Haggard, who

recorded it in January of 1973, but issued the following holiday season. It became a country #1 hit and was

Haggard's only pop top 40 success.

Writer and friend John Mackie, who all will recall did the lovely liner notes for “On The Floor Of Heaven,”

told me he thought the two recordings of “If We Make It Through December” and “Run, Run, Rudolph”

were, for him, emblematic of the two sides of the Blue Shadows. I think I remember Dave Chesney

encouraging us to get a couple of Christmas tunes together and, in our efforts to select songs we had to deal

with my happy agnosticism. “If We Make It Through December,” a beauty of Merle Haggard’s, came to us

from either Bill or Dave. I know a lot of Haggard but I hadn’t heard this one. It suited our purposes

perfectly and was a great Billy-style tune. I came up with Chuck Berry’s “Run, Run, Rudolph,” though I

wanted to change the lyrics. I led the un-Christmassy charge and Bill helped with the lyric re-write. Both

went over very well live.

“Raised On Robbery” – previously unreleased by The Blue Shadows. Written by Joni Mitchell in 1973

and released the following year on her LP Court & Spark. The Band's Robbie Robertson played guitar on

Mitchell's session, which became a top 40 Adult Contemporary hit in the U.S.

We had a brief fit sometime in ’95 where we decided to learn some tunes by Canadian giants whom we

admired. Joni Mitchell’s “Raised On Robbery” was great fun to play live and it led us to consider others.

Soon we had Michel Pagliaro’s “What The Hell I Got” and then we got too busy on the road to learn our

other planned-for tunes: Leonard Cohen’s “Tower of Song” and “You Were On My Mind” by Ian and

Sylvia. Shame.

“Soldier Of Love” – Previously released on The Blue Shadows EP Rockin', released in 1994. Credited to

writers Buzz Cason and Tony Moon and originally recorded in 1962 Arthur Alexander (1940-1993). The

Beatles performed the song in 1963 on a BBC radio show and acts as diverse as Marshall Crenshaw and

Pearl Jam have essayed their own renditions. The Blue Shadows also included Alexander's "If It's Really

Got To Be This Way" in their live repertoire.

We loved doing this song. Those who love Arthur Alexander are a rare army. People have to dig to

discover him because he wasn’t a big recording star and never even, as far as I know, appeared on

television. Others did Alexander’s tunes with great success so those who discovered him were usually

young musicians who, as Bill and I had been, read album covers obsessively as kids. In the pre-Blue

Shadows band we often did Arthur’s “You Better Move On” and “Anna” even though he was still alive at

the time (see “dead guys,” above). That’s how good Arthur Alexander is.

“What The Hell I Got” – Previously released on The Blue Shadows EP Rockin’ released in 1994. A

fondly remembered single by Canadian artist Michel Pagliaro. Pagliaro is one of the few Canadian artists

to have hits in both French and English. This song originally appeared on his 1975 Columbia LP Pagliaro

I.

Part of the Blue Shadows Canadian pavilion, as I mentioned. It went over very well in Montreal, I

remember, as did our French translation of the bridge to “Coming on Strong.” No, we weren’t running for

office; it seemed like it would be a nice tickle to do, and it was.

“Hell Stays Open All Night” – Released as the b-side to the original vinyl 78 rpm promo release of

"Coming On Strong." Credited to writer Bobby Harden and originally recorded by George Jones in 1990

as the lead-off track for his album You Oughta Be Here With Me.

Very early days when the Shadows were finding their feet. Bill was very much the lead singer and this

George Jones tune suited him well. I think Dave brought it to us. Following the completion of all

instrumental tracks it was felt that the song’s tempo was too fast. We had no time to redo it before we had

to hit the airport and resume touring so we (ssshhh!!!) slowed the tape down to a speed that sounded right.

Bill then did the lead vocal in the new key and then he, Elmar, and I did the background vocals, and we

called a taxi. BTW: a similar but not identical thing occurred during the recording of “Tell Me,” on the

“Lucky To Me” album. That time, after all recording including the vocals was done, it was felt the tune was

too slow. Forgetting that the vocals were already completed, that in fact the song was already mixed, we

asked our engineer and producer to speed it up to I-forget-how-many-more-cycles per second. We then

stopped thinking about it. When it was time to master the recording we treated it like the rest of the tunes.

Bill and I realized at a very late date that we were putting out a speeded-up recording that made us oldtimers

– I was about 37 and Bill 48 – sound like the teenaged Don and Phil Everly. So there they are: two

quite musical though slightly fraudulent representations, here revealed. We didn’t have this conversation.

* italicized cover song notes by Paul Cantin

|

|

On The Trail of The Blue Shadows

by Paul Cantin

In telling the tale of The Blue Shadows, let’s start off by dispensing with the notion that opposites attract.

When it comes to making great art, it isn’t so much that opposites are naturally drawn together.

Circumstances can take disparate elements and nudge or thrust them towards each other, and when they

come into contact, sparks may fly. When expatriate American wayward teen sensation Bill Cowsill met

Canadian roots rocker Jeffrey Hatcher to form the core of The Blue Shadows, sparks did fly. The pair was,

to say the least, a study in contrasts. But the music they made together synthesized their unique

perspectives into some indelible, timeless music.

The great creativity that results from that collision of opposing sensibilities can be thrilling for the audience

even if, at times, it can be harrowing for the participants. But when everything seems to work in spite of

those differences, in spite of all the internal and environmental obstacles, the travails of making great art

fall away and we’re left to celebrate the art itself.

In 2010, it is now possible to step back and appreciate what The Blue Shadows accomplished in their short

time together in a manner that may not have been possible in the more than 15 years since the group

released its debut long player, On The Floor of Heaven. Listening now to the record’s 12 original cuts and

the bonus tracks gathered here for this deluxe edition, it’s clear that The Blue Shadows emerged in the early

90s into a kind of purgatory. Had they surfaced in the 60s or early 70s, before the Balkanization of radio

formats, their mix of trad Nashville and Mersey pop would have found a perch in the hit parade of the day.

Likewise, if they were starting out today, the alt-country movement would very likely be celebrating The

Blue Shadows’ uncompromising bloody-knuckled sound.

Unfortunately, The Blue Shadows launched into the era of Garth Brooks and Shania Twain, when country

music was fusing with MOR and arena rock, turning its back on tradition and rushing toward a numb,

neutered form that negated the grit of country music even as it embraced the superficial iconography – all

hat, no Hank. To borrow a later Blue Shadows song title, they were born into a time out of place. The group

is gone, but maybe now is the time to put The Blue Shadows’ achievements into its proper place.

In late1990, Jeffrey Hatcher arrived in Vancouver, British Columbia as a journeyman guitarist; singer and

songwriter who’d already had a couple of swipes at grabbing the brass ring. In the late 70s, he and his

siblings Paul (drums) and Don (guitar, sax) and childhood friend Dave Briggs (guitar) caused a sensation in

their hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba as The Fuse. In the 80s, the group relocated to Toronto and

reformed as Jeffrey Hatcher & The Big Beat, recording and producing a minor hit LP entitled Cross Our

Hearts (released by indie Upside Records in the U.S. and CBS in Canada) and scoring a hit single entitled

“The Man Who Would Be King.” Management issues snarled their attempt to release a follow-up album,

and by the time he arrived in Vancouver, Hatcher was searching for a new direction.

“I wasn’t sure if I had another band in me or not,” Hatcher recalls of that time. It so happened that around

1992, Rosanne Cash was performing in Vancouver and Hatcher (via an old contact with her manager)

convinced the promoter to let him open the show as a solo act, but he could not rent a guitar without a

reference from a fellow musician. Hatcher dialed his pal, guitarist Danny Casavant1, who vouched for him.

During the conversation, Casavant casually mentioned he was about to leave a local group. Perhaps

Hatcher was interested in taking on his spot with Billy Cowsill?

Coincidentally, shortly after Hatcher had arrived in Vancouver, he had looked up an old music business

contact of his named Larry Wanagas, who likewise had recommended Hatcher check out Cowsill’s act.

Hatcher first met Wanagas back in the late 70s when The Fuse was touring Western Canada and Wanagas

1 Casavant would later contribute guitar to the track “If It Ain’t Rockin’” from On The

Floor of Heaven.

was working as a promoter and later, studio owner. “They were the first band I ever extended credit to,”

recalls Wanagas, adding Hatcher and company did eventually repay their debts for the recording session. In

the intervening years, Wanagas had moved into management and was in the process of stewarding k.d. lang

from a Prairie country-punk novelty act into a multi-platinum star. He had also taken on Cowsill as a kind

of project to see what could be done to revive his career.

“I knew Bill and Jeff both came from that background of being in family bands. I just had this feeling that

they could sing together and play together. There was no real plan beyond trying to get these two together

and see what might happen,” says Wanagas. Some weeks later, Hatcher was finishing an early Vancouver

club gig with Billy Cowsill when, for reasons never identified, an ornery patron approached Cowsill and

expressed both his displeasure with the singer and his desire to settle the matter with fisticuffs. Cowsill

responded by picking up his acoustic guitar and hammering the fellow’s head.

“Billy gave him a wood shampoo with a Takamine,” “He laid him out on the dance floor and they dragged

him out by his boot heels and dumped him in the street.” recalls Dave Chesney, who came on board with

Wanagas to co-manage the group.

Hatcher told Chesney and Wanagas that he was alarmed. Was this going to be a regular feature of his new

life as sideman to Cowsill? Totally out of character, the managers assured the new guitarist. You could gig

with Billy Cowsill for 100 years and something like that will never happen again. Reassured, Hatcher

returned for the next night’s performance. Like clockwork, a friend of the previous night’s victim came

after Cowsill hell-bent on payback, with predictable results.

“Billy coco-bonked him, too,” Chesney says. “Two nights, two guitars.”

It would be hard to contain the full life of William Cowsill Jr. here and even harder to exaggerate the ups

and downs of his tumultuous life. Born in 1948 in Middletown, Rhode Island, Cowsill was the eldest

member of the singing family band known as The Cowsills. Considered by some the quintessential

bubblegum group of the late 60s and early 70s, The Cowsills earned an indelible spot in pop history with

the million-selling “The Rain, The Park And Other Things.” Although the siblings (including mom

Barbara) sang, it was big brother Bill who performed lead on that signature song. The group served as the

model for The Partridge Family TV series; David Cassidy’s character was modeled on Bill. Other chart

songs would follow, along with numerous TV appearances, tours and a milk marketing campaign built

around their wholesome looks. They landed appearances on The Tonight Show, American Bandstand,

Music Scene, Playboy After Dark and the zenith of TV variety shows in that era, The Ed Sullivan Show.

But Bill chafed at the group’s teenybopper image, and after he was caught smoking pot in 1969, he was

fired from the group and (as Bill often joked) booted from the family. He fell in with a coterie of LA

musicians (including Waddy Wachtel and Warren Zevon2) and was subsequently asked to sub for Brian

Wilson on tour with the Beach Boys; Cowsill said he turned the gig down after being warned off by a thenbed-

bound Brian. Cowsill set out on an odyssey that took him to Tulsa, where he played with J.J. Cale.

Then to Greenwich Village where he ran with Joe Ely, next on to Austin, and then returned to LA where he

worked for a time as a session musician. In 1971, he cut an eccentric pop album for MGM entitled Nervous

Breakthrough, which failed to break through.

He drifted up to Canada and made his living gigging with country acts in Alberta and working for a time on

big rigs plying the northern ice highways before relocating to Vancouver and recording with the countryrock

band Blue Northern. Then as a solo act, accompanied by upright bassist Elmar Spanier and some

occasional side players, he developed a following in Western Canada performing the “Dead Guys Set” –

covers only by artists who had left this mortal coil.

2 In 2000, I asked Zevon about his relationship with Cowsill. Zevon was silent for about

10 seconds and then answered in a flat, unreadable tone: “I knew him.” Next question …

He was, by some accounts a deeply troubled soul, but his love of music was undiminished by the hard

times and hard luck. “Despite his foibles and ups and downs, he always got work,” says Chesney. “You

could put him in a corner with a guitar and a PA and he could go for hours on end. He’d sing Elvis Presley,

Roy Orbison, and The Beatles. People sat there slack-jawed. There was always that recognition -- the fallen

star. But nobody really held a lot of pity for Billy unless they dealt with him on a personal level because

when he went onstage, he would destroy the place.”

“I had heard he was a wild man with a golden voice. And he was all that,” Hatcher recalls of meeting

Cowsill. “He was funny and savvy. Intelligent. Fun to talk to but erratic, his attention was all over the

place. He was kind of crazy but kind-hearted.”

After the back-to-back guitar-smashing gigs, however, Hatcher was uncertain about their future. “It was

brutality. I thought, this guy has horseshoes up his butt. How has he not been killed? It was outrageous

behavior.” They made for an unlikely pair. Hatcher, at that point in his life, enjoyed a comparatively

healthy lifestyle and laid-back demeanor. Rail-skinny Cowsill subsisted on nicotine, caffeine and not much

else that was healthy. But they were prepared to forgive each other their differences for one simple reason.

They found they could make some great music together.

“Knowing the two of them as I did, and being fans of their talent, I felt there was something simpatico

there,” says Wanagas. “They shared that thing of singing with siblings and their taste in music was very

similar.”

Hatcher and Cowsill shared a common love of the sounds of the 50s and 60s. As they began to harmonize

together, they locked into a tight, intuitive blend that usually requires shared DNA. Hatcher remembers the

moment when they hit on that sound in the dressing room of a Vancouver club. “I played Billy this song

and when we got to the chorus, he did the harmony above that. He got it. It sounded fantastic. It was a

country tune, a pop tune. It was the Everly Brothers and Hank Williams and all these things together. I

probably slapped him and said ‘this is exactly what it should sound like. Let’s keep doing it!’”

As Hatcher stepped up his role in the group and the combo morphed from a Cowsill support band into a

group entity of its own, the change in Cowsill’s demeanor was notable. “He became Mr. Love after that. He

started to turn on the charm. It became more of a two front man act. He was the golden voice and we were

the harmonizing duo,” says Hatcher. Wanagas suggests it was more than just a change in attitude that gave

Cowsill cause to smile more often; after years of negligent dental hygiene, Wanagas paid for Cowsill to

have his teeth fixed. “You’ve never seen someone so eager to smile once those teeth were fixed,” Wanagas

recalls. “He just couldn’t stop smiling.”

With drummer Jay Johnson and Spanier on bass (later replaced by Barry Muir, a former member of

Canadian hit makers The Payolas and Barney Bentall & The Legendary Hearts) it was obvious this could

no longer be simply the Billy Cowsill Band. Always a fan of astronomy, Cowsill first offered up the name

The Blue Stragglers, after a phenomenon defined by Wikipedia thusly: “The merger of two stars (which

would) create a single star with larger mass, making it hotter and more luminous than stars of a similar

age.” Cowsill explained that blue stragglers were actually the reflected light of stars that had already died.

“I thought that might be hitting a little too close to home,” Chesney laughs. In the end, they settled on The

Blue Shadows. Hatcher’s partner, the artist Leah Decter, suggested the name, after the old Sons of the

Pioneers number “Blue Shadows on the Trail,” which had become a favorite after Syd Straw’s cover

version on the Disney tribute album Stay Awake. Straw’s recording would later become The Blue Shadows’

“walk-on” music, pumped through club and theatre P.A.s as the band took the stage.

Onstage they evolved into a nimble, versatile outfit. Their sound hit a middle ground between hardscrabble

country and chiming 60s pop. Covers included The Beatles’ “Anytime At All,” George Jones’ “Hell Stays

Open All Night,” Canadian cult rocker Michel Pagliaro’s “What The Hell I Got” and Joni Mitchell’s

“Raised On Robbery.” When asked to define their style, they called it “Hank goes to the Cavern Club.”

Alone at the microphone, Cowsill could summon a voice that brought to mind both Hank Williams and

Roy Orbison. When Hatcher joined in their voices locked and soared. The rudimentary rhythm section

(including Cowsill’s driving acoustic guitar) pumped like a piston as Hatcher coaxed simple, melodic,

tremolo-laden melodies and stinging solos from his custom made hollow body guitar (dubbed the “Henry

Guitar,” and a hand-crafted creation of Hatcher’s partner Leah Decter).

Hatcher and Cowsill began writing together, too, and their contrasts were, at least for now, complimentary.

If Cowsill was a zoom lens, instinctively drawing from a personal well of sadness or joy, Hatcher was

wide-angled, looking for opportunities to transform those personal perspectives into something more

universal. “Is Anybody Here” starts as a solipsistic cry from the heart, but by the end converts into a

broader social observation. Cowsill’s seed for “Don’t Expect a Reply” (a song which would later surface

on The Blue Shadows’ sophomore effort Lucky To Me) used the runaway train cliché to assert his bad-ass

stature; Hatcher used the later verses to comment on manifest destiny, linking hell-bent, personal

destructiveness with the history of rapacious westward expansion: “I used to roll on through when it was

countryside/Then the cities they grew until they reached the sky.”

Bumstead’s Vancouver office was large enough that it contained a small recording studio, which served as

the band’s woodshed for rehearsals, songwriting, demoing and early recordings. As they assembled original

material, much of the recording was conducted in March 1993 at Bullfrog Studios in Vancouver.

Their debut album On The Floor of Heaven arrived in 1993, and it still sounds like it dropped from another

era. The lead off track “Coming On Strong” erupts on a surge of sawing fiddles, Hatcher’s chugging guitar

and some sly wordplay. “When Will This Heartache End” could serve as a model for simplicity and

elegance in pop song craft. Hatcher resurrected “Deliver Me,” a song from his Big Beat days; Cowsill’s

gravitas found new depth in the song, which became a Blue Shadows’ single and the subject of a moody,

evocative music video.

Before the album’s release, the group traveled to Nashville and played a showcase at 12th & Porter. “The

band went onstage and it was the who’s who of the music industry and they absolutely burned it to the

ground,” recalls Chesney. “If there was a moment I had where I thought things are about to change for us,

that was it.” Sony in Canada issued the album via Wanagas’ Bumstead Records, but a U.S. release

remained elusive.

At South By Southwest in 1994, the response was equally enthusiastic. Cowsill and Hatcher were invited to

perform at a later charity concert in Santa Monica in honor of the Everly Brothers. Amid a cast packed with

heavyweights (including Dave Alvin and a taped performance by Brian Wilson), the pair performed a brief

acoustic set that received a riotous response and the evening’s only encore. They toured with The Band

(which had reunited sans Robbie Robertson) and opened for groups as diverse as the Barenaked Ladies,

Sweethearts of the Rodeo, J.J. Cale, multi-platinum contemporary Celtic act The Rankin Family and

Barney Bentall & The Legendary Hearts. The Blue Shadows appeared on TV in Canada and garnered

critical raves across the board.

And yet, no U.S. release. The Blue Shadow’s tour T-shirts carried a motto: “Low Tech, High Torque,” But

modern country music, at the time infatuated with line dancing and New Country gloss, betrayed a different

attitude: High Tech, Low Standards. Label personnel would tell Chesney that they loved the band and

asked that he send them a copy when they did sign with a label. But none of those execs stepped forward to

release it themselves. Says Chesney: “The resounding response (from Nashville) was: ‘I love this band, but

they scare me.’”

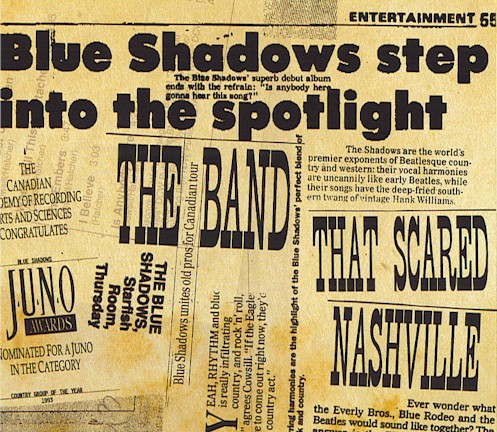

It’s a measure of the group’s defiant attitude that they embraced rejection as an indicator that they were on

the right track. After the comment from the label exec about fearing the band, The Blue Shadows’ tour

posters billed them as “the band that scared Nashville.” When a well-known, veteran Music City figure

declined to sign the group because they struck him as “too retro,” Wanagas and Chesney pressed up

promos for The Blue Shadows’ first single, “Coming On Strong,” as vinyl 78 rpm singles. “It was our way

of saying: ‘You want retro? We’ll give you retro,’” laughs Wanagas.

Yet for the people who did get to hear The Blue Shadows, the experience was anything but menacing. As

they crisscrossed Canada and ventured occasionally into the U.S., the band made an instant connection with

those who took the time to listen. Chesney describes how fans repeatedly took the time to approach him

and the band after gigs with a similar story: they had been searching for music like this for years and had

begun to despair that someone, somewhere might write ‘em and sing ‘em and play ‘em like that anymore.

“What we were making was tunes for the tuneless,” Chesney says.

When they ventured out on the road, the quality and kinship brought by the music wasn’t always confined

to the stage. In Ottawa one night, Hatcher, Cowsill, Chesney and a coterie of acquaintances lingered over

dinner at a restaurant in the Byward Market. Talk of music led to guitars being pulled from cases as

Hatcher and Cowsill dipped into their well of shared songs, harmonizing and playing in the otherwise

deserted restaurant – first for their tablemates, then gradually for the manager, the waiters and – one by one

– the kitchen staff. Beatles and Hank Williams and Everly Brothers songs, combined with some Blue

Shadows originals, filled the empty restaurant for hours. It was as if nobody dared speak for fear of

breaking the musical spell.

Hatcher would sometimes refer to Cowsill as “Friend of the Service Industry” for his decorous treatment of

waitresses, chambermaids, gas jockeys, convenience store clerks and the like. On the road late at night,

Chesney would often spot Cowsill’s hotel door propped open, a collection of hotel staff gathered in

Cowsill’s room as the singer told stories or sang songs.

A second album, Lucky To Me, was released by Bumstead in 1995 and licensed to Sony Canada. But by

then some of the characteristic differences between Hatcher and Cowsill began to catch up with them.

Many of the ghosts that had haunted Cowsill throughout his life came back in force. It impacted the music

and ultimately their bond.

In 1996, The Blue Shadows disintegrated. A ready-for-release live album was shelved at the last minute

and remains in the Bumstead vault along with a cache of other live shows, demos and outtakes. Hatcher

went on to earn a Bachelor of Music Therapy degree and a Master’s degree in Counselling Psychology,

eventually finding rewarding work as a music therapist in Winnipeg, helping troubled youth overcome their

social and psychological challenges through the act of making music.

Shortly after the break-up of The Blue Shadows, Cowsill descended deeper into his darker side and burned

many of the bridges to those who had supported him through the years. It may have ended there, but

something miraculous happened. Against all odds, and with the help of his friend Neil MacGonigill

(proprietor of the Calgary-based indie label Indelible Music), Cowsill turned his life around. He relocated

to Calgary and got control of his demons. He put on weight and appeared healthy and happier than he had

been in years. He worked with a new band, the Co-Dependents, released two albums and became a guru to

young musicians. And then just when he had his mental and spiritual house in order, fate delivered a cruel

blow. He suffered Cushing’s Syndrome (an over-exposure to the hormone cortisol) and severe

osteoporosis. Back surgery left him with a permanently collapsed lung and the brittleness of his bones left

him with two broken hips. Perhaps most harshly, he also developed emphysema, which required the use of

an oxygen tank to breathe and made singing especially challenging. Then in early 2006, Billy received

another blow. The body of his brother and family band mate, bassist Barry Cowsill, had been recovered in

the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

As his illnesses conspired, Cowsill reconciled with Chesney and Hatcher. “I wrote to Bill to see how he

was doing, but the spark for it was my hearing of his brother Barry’s death. Bill and I had both performed

for years with siblings and I felt for him particularly because of that bond,” Hatcher says. Cowsill phoned

Hatcher to respond to the letter. The two spoke for about 10 tearful minutes. “He sounded like he was on

his way out. He sounded like he wasn’t going to last much longer. It was a very sweet conversation, and I

had a good cry after we hung up,” Hatcher recalls.

In February 2006, the very day Cowsill’s family and friends were scattering Barry’s ashes in their home

state of Rhode Island; they received news of Billy Cowsill’s passing.

Just weeks before his passing, Cowsill gave his last-ever interview to me for a story I was working on for

No Depression. His voice was weak but his mind was still alert. When I asked him to reflect back on the

work he was most proud of in his long career, he did not hesitate: “On The Floor of Heaven,” he said,

adding he was saddened that the set was at that point no longer available and he hoped someone would see

to it that the music had a second chance to find an audience.

“To my mind, that is the finest piece of work I ever did. It is just so good. The writing is so good. The

production is so good. It is a nice little piece de resistance,” he said.

And so, in fulfillment of Billy Cowsill’s request, here once again -- and for many listeners, now for the first

time -- is The Blue Shadows’ piece de resistance – On The Floor of Heaven. Now with even more tunes for

the tuneless.

Paul Cantin

Toronto, February 2010

Paul Cantin was a contributing editor with No Depression magazine and maintains a music blog at

NoDepression.com. Elements of this essay were originally published in No Depression.

|

|