The Lost Cowsill

February 3, 1992

Newday

New York, New York

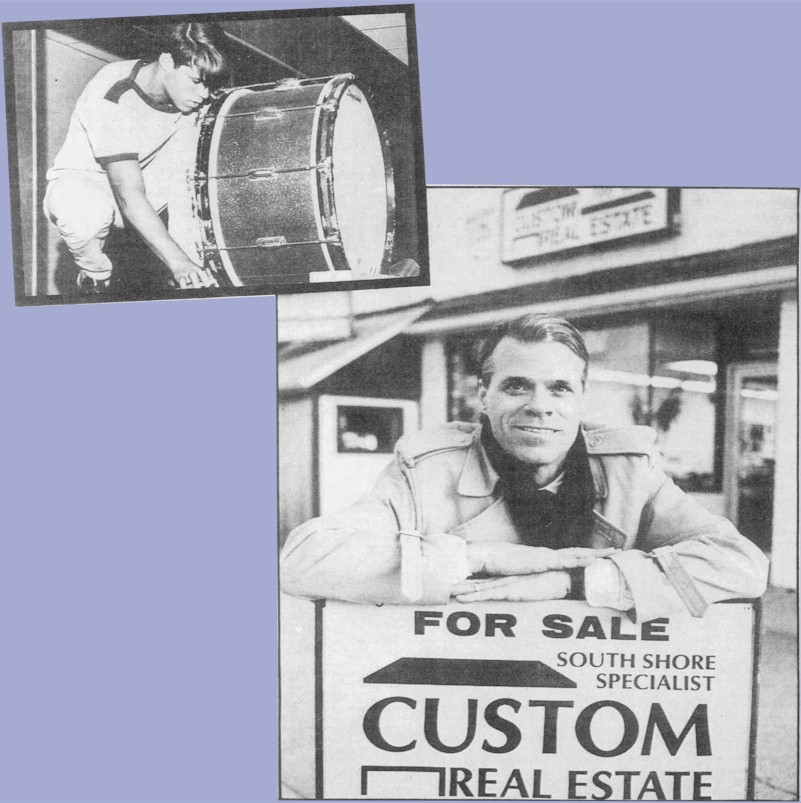

Richard, drummed into handling the equipment in his family's heyday in the '60s, left, sells real estate today while dreaming of a singing career.

|

|

A story of dreams, fame, betryal, real estate, teenyboppers, Ed Sullivan, Howard Stern, the rain, the park and other things.

Decked out in suede boots and a blonde ponytail, Richard Cowsill bounds into the tiny conference room of a real estate office in Massapequa, clutching a videocassette as if it were a crucial courtroom exhibit.

"What you're going to see," he explains, slipping the tape into a VCR, "is a spectacle of men with gray hair acting like six-year-olds."

He leans forward in his chair like a zealous prosecutor, his eyes never straying from the TV screen. On it, three men and a woman, all of whom have Richard's deep-set eyes and prominent jaw, giggle and banter with Joan Rivers. It's the Cowsills - remember the Cowsills? - chatting about a comeback. The Cowsills, who once upon a bubble-gum time reigned supreme among America's teenyboppers. The Cowsills, who clocked out on their 15 minutes of fame, long ago, their hits of the Sixties, songs like "Hair" and "The Rain, the Park and Other Things," now campy relics of the Wonder Years.

Joan Rivers' studio audience titters at her guests, now middle-aged and still perky. But the brother on Long Island watches the tape stone-faced. This is, after all, the talk show that broke his heart.

"Lie!" Richard Cowsill snaps at the screen, as one of his brothers tells a family anecdote, something about a golf course. "I'll give you the real story."

"No, Susan, wrong!" he corrects his sister.

"Lie!"

"No."

"No."

Richard cannot bear it. The obfuscation! The revisionist Cowsill history! "We never owned an eighteen-hole golf course," he says dismissively. "That's so asinine."

He's so hepped up he has to leave the room. The thing is, his brothers and sister did not invite him to appear with them on "The Joan Rivers Show," did not even tell him they were going to be on. He had been excluded from the group the first time around - his father told him he was a lousy singer, he says, and the rest of the family accepted the judgment. And now they were keeping him our again. How could they do this? He's been told, he says, that finally, he would be accepted as a full-fledged Cowsill. For the first time in his life he would sing on stage with his brothers and sister, fulfill his Cowsill birthright. No more backstage gofer, consigned to schlepping the luggage. Not this time. Promises were made, he insists. He has letters.

The "Joan Rivers" appearance showed him the bitter truth. He was not going to be part of any Cowsill comeback. "I was hurt," he says. "I had thought that we were going to be a family for the first time in our lives."

And so, Richard Cowsill, 42-year-old hyper kinetic family man, real estate salesman, budding rock impresario, contractor, Vietnam Vet, recovering drug and alcohol abuser, came to a fateful decision. If he couldn't sing with them, he'd sing without them. He signed on with a manager and is now working with a musical director. Acting lessons? Absolutely. Publicity? Well, if being a Cowsill is no longer enough, maybe you'd care for some dark stories about how dysfunctional the Cowsills really were. Howard Stern cared: Richard was on for hours. The Star cared: It ran an interview with Richard in December about his father headlined "Bubble-gum Beast!"

Is nothing sacred on the path to fame? Richard knows he is playing with unfriendly fire: His brothers and sister won't comment on his allegations that his father beat them frequently as kids - particularly Richard - allegations corroborated by the publicist who toured and lived with the Cowsills at the height of their popularity, from 1967 to 1970.

Stern, the noted radio shrink, thought he had found the key to Richard during an appearance on his morning show last June. "You know what's hurting you?" he said. "The Cowsills had this phenomenal success, they're part of pop culture. And you say, 'Hey why wasn't I allowed in this?' "

But Richard insists he's not bitter. He says he's not asking much. All he wants is the adulation of millions and a house on the water.

"You decide: 'I'm going to do acting, singing and I'm going to be a huge success,' " Richard says, exuding confidence as he sits in the kitchen of his modest rental house in Merrick. "It's that simple. It's determination, my friend. You've got to have whatever it is, and I've got it."

This, then, is the story of the singular trip that is the life of Richard Cowsill, a man who, as a matter of family pride and honor, wants more than anything to be a Cowsill. Pull up a beanbag chair It's going to be a bumpy tale.

Try to imagine it: All of your brothers, your kid sister - even your mother - are the pop icons for hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of American teenagers. Their group is so hot that the American Dairy Association ask them to endorse milk. They're in Vegas, playing for Elvis, they're in Rome, They're on "The Ed Sullivan Show" . . .

It gets worse. One of them is your 18-year-old twin brother - your twin brother! - and he is a drop-dead teen heartthrob. The magazine 16 chronicles his life, as well as the lives of your little brothers, as if they're the Beatles or the Stones or the Lovin' Spoonful. You learn from the pages of the magazines that Bob, your fraternal twin, is careful with money, loves to wear hippie beads and "does not mind aggressive girls, as long as they are ladylike."

And where are you? You show up in the publicity photos from time to time. You're the fuzzy one in the background, plugging in the amps.

That is what adolescence was like for Richard. He was the only Cowsill kid who didn't get to play in the group or endorse milk. He never even got onstage. That decision, he says, was made by his father, Bud, a former Navy man who, by all accounts, ran the group as if it were a military unit, simply refusing to put Richard on the front line.

No one can fully explain it. Was he simply an untalented Cowsill? Richard says he doesn't know how much talent he had, because he never got the chance to show it. "My father did not like himself," he says. "He saw in me himself, and he took it out on me. The other school of thought was I stuttered, and it was an embarrassment for him."

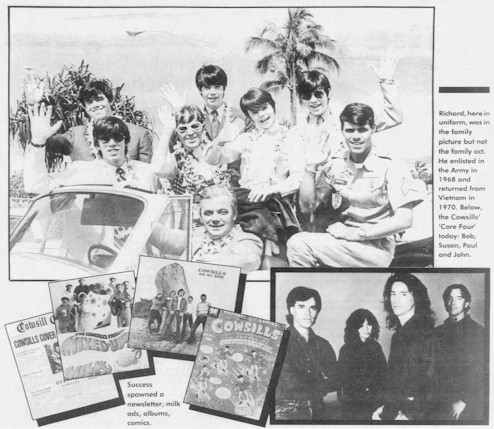

And so, dressed in suits and ties or matching Nehru jackets, Bob, Paul, John, Bill, Barry and Susan and their "mini-mom," tiny Barbara, sang in spectacular harmony onstage. (Bob, Paul, John and Susan keep the group alive today - the so-called "Core Four.").

In those early years Richard, known then as Dick, worked backstage, packing equipment. Rich, as Janis Murray, a Manhattan press agent who was the Cowsills' live-in publicist for three years, called him, "was the roadie, the chauffeur. He was the gofer."

"I was Cinderfella," Richard concurs with a throaty laugh. "There were two separate worlds. There was behind stage and onstage. If I would go up while they were signing autographs, I was told to get back to work."

Even Bob Cowsill, who would not talk in detail about his brother, said in a phone interview from his home in Los Angeles that Richard's childhood was anathema to him. "I can't imagine what it was like, to be backstage, when we were on 'Ed Sullivan,' " he said.

To anyone who was not in junior high or high school in 1968, the Cowsills might not even provoke a half smile of recognition. They were specific to a time and place. Their rise was meteoric; a few years later they sank without a trace.

The group's roots were in Newport, R.I., where they had gained a following, playing fraternity parties at nearby Brown University. They hit it big in 1967 with their first release, "The Rain, the Park and Other Things" - which went all the way to No. 1 on the pop charts - and solidified their success with a string of hits that included "Indian Lake" and "Hair," their sunny version of the title song of the 1967 protest musical: "Give me a head with hair . . . Long beautiful ha-air . . ."

The irony, of course, was the Cowsills were cleaner-cut-than-thou, with thick, dark hair that barely brushed the tops of their ears. In music and appearance, they were the quintessential purveyors of bubble-gum pop, a label many of them grew to detest.

But the Cowsills' saccharine image honed and maintained by father Bud, paid off fabulously. They had a 23-room house in Newport, apartments in New York and a mansion in Santa Monica, Calif. They owned a campground in Rhode Island and an airplane. Their success was out of an American fairy tale: There was a Cowsills comic book, Cowsills posters, Cowsills T-shirts, even a Susan Cowsill doll. They recorded the theme song to "Love, American Style" and were the model for the hit TV sitcom "The Partridge Family."

"They were like the New Kids on the Block of the Sixties," says publicist Murray, who estimates the family earned $10 million to $15 million in a few years.

|

Richard, here in uniform, was in the family picture but not the family act. He enlisted in the Army in 1968 and returned from Vietnam in 1970. Below, the Cowsills' 'Core Four' today: Bob, Susan Paul and John.

Success spawned a newsletter, milk ads, albums, comics

|

|

Lynne Margosian was 13 years old in Long Island City when she first laid eyes on them. It was September, 1967. "The Ed Sullivan Show." It was kismet.

"I think I saw them twenty-eight times in concert," she says. "It was like crazy."

Her husband, Ed, with whom she now lives in Freeport, rolls his eyes as Margosian talks about her Cowsills years. She still loves them, still subscribes to the Cowsill fan club newsletter, The Cowsill Connection, which was revived recently. She has a world-class collection of Cowsill memorabilia, and Richard says, "She knows more about my family than I do."

"I had every article about them that was ever written," Margosian says. "I was obsessed."

But not with Richard. How could she be? He was the invisible Cowsill. Occasionally his picture cropped up in a magazine, usually because he was in the wedding of one of his brothers or because the childhood photos of Bob included his twin. "You knew he was in the Army," she says, referring to Richard's enlistment in 1968. "It was in the teen magazine and stuff."

Janis Murray says she knew Richard craved attention. She managed to persuade Bud to let her send out some publicity photos of him. "Rich would be like a wounded puppy," she recalls. "He was always made to feel as if he wasn't good enough."

For Richard, the acclaim of multitudes remains as much an abstraction as it is for Lynne Margosian. One of his fondest memories is the day he was mistaken for a rock star. The Cowsills had a guest spot on a children's show at CBS' Manhattan studios on the same day that Herman's Hermits were in town. His brothers had arrived at the studio. He brought up the rear. When he got to the stage door, he says, the fans gathered there thought he was Peter Noone, the Hermit's lead singer.

He remembers standing there, signing the fans' autograph books giddily. The stolen moment was all his. Until his father saw him and told him to hop to it.

Still, there was the moment. "It was," he says "the most wonderful feeling I had every felt."

In the kitchen of a modest cottage in South Bellmore, the Man Who Would Be Cowsill is doing a series of one-handed push-ups on the floor.

Richard the real estate salesman is here to get a listing. But Richard the would-be entertainer never stops performing.

"And I'm going to be a grandfather," he boasts of his calisthenic prowess. (His pregnant daughter, from his first marriage, lives in Las Vegas.) "You do just one!"

The homeowners just sort of stare blankly, so Richard springs to his feet. "Well, kids, that leaves only one thing," he says, laying a four-page contract on the kitchen table. "You know that in the real estate business, agents are motivated by greed . . ."

Twenty minutes of schmooze later, Cowsill closes the deal. The young couple agrees to let him sell their house. And not only that: He's persuaded them that a 7 percent commission, higher than normal, is just the inducement he needs to find a buyer for their little house on the canal.

"You better get out there and sell your rear end off," the wife says.

Cowsill flashes his most ingratiating Eddie Haskell grin. "Ma'am I'm out there making other people's dreams a reality." Then he cracks up. "Oh God," he says. "Where did I get that one?"

Richard Cowsill is a born salesman. Everybody says so. Even in his drug-crazed years, the years after Vietnam, when he came out of the Army addicted to heroin. Bud had demanded that he enlist, he says, after a fistfight in their New York apartment. Years later, he would watch a tape of a Cowsills TV special in which his little sister saluted her big brother in Vietnam.

After coming home in 1970, Richard did not return to his family. Instead, he claims, he visited military bases, selling bags filled with chocolate cake mix to unwitting servicemen. He told them it was mescaline. "Military guys were the dumbest group in the world," he says.

The scam, he says, supported his drug habit, which remained heavy throughout the '70s. When he emerged from the fog, he went to college in California on the GI bill, got work in construction and ultimately met a woman from Massapequa who would become his second wife and help him stay off drugs. He says he was been drug free for seven years.

The future Susan Cowsill was a dental assistant in Southern California when they met in 1982. Fourteen years younger than Richard, she had never even heard of the singing family to which her husband-to-be had so desperately wanted to belong.

By the early 1970s, after making eight albums in four years, the Cowsills had become history, their millions frittered away in what Richard and other family members have since described as poor investments and management.

In the years that followed, the siblings went their own ways. Some of them didn't see or speak to each other until they were reunited at the 1985 funeral of their mother, who died in Arizona of emphysema. While several of the Cowsills had drifted in and out of show business, Richard stayed in construction. He and his wife had moved to Arizona to help take care of his mother and later left with their son, Bryan, now 5, to live in Susan's native Massapequa.

"Life with Richard has been many things," observes Susan, who seems his opposite in temperament, cool and reserved. "Good, bad, up, down, happy, sad. But I'll tell you one thing. It has never been boring."

On Long Island, Cowsill supplemented his construction business by setting up a delivery service for a South Shore deli. He drummed up 150 customers, but he wore the deli man down. "He is some B.S.-er" says the deli man, who asked not to be identified. "He kind of grinds on you . . . I told him, 'If you can sell someone a bologna sandwich, you can sell them a house.' "

On a Friday afternoon in January, a prospective home buyer from Queens is sitting on the couch in Custom Real Estate's office on Sunrise Highway in Massapequa.

She is here for her first meeting with Richard. She has told him she wanted to look at houses in the mid-price range. He had informed her of his connection to rock history.

"Really? The Cowsills?" the woman ask, as her 4-year-old daughter plays at her feet.

"Yes," he says, adding in his best baritone: 'Hair! Long beautiful ha-air.' "

Richard brings the Cowsills everywhere, even to the streets of Biltmore Shores, where he is trying to sell the woman a house. "I discuss your needs and facilitate your desires," he tells her, and then rolls his eyes.

The woman is amused, but her little girl doesn't get it. "Mommy," she says from the back seat of Richard's Pathfinder. "That man talks too much."

His bosses, however say that Richard has real potential in real estate. And why not? He as bred to facilitate, backstage or backyard.

"You could ask him to sweep the floor. He is a mensch," says Mel Adler, a former radio executive who runs a pay-per-view rock-concert service called Skybox. He tells a story about Richard, who works for him part-time as an associate producer. After a concert they taped at the Palladium in New York on New Year's Eve, Adler had expressed a craving for a cigar. Richard disappeared into the night and returned with two Garcia y Vegas.

The next day, nursing a hangover at brunch, Adler remembered leaving the cigars somewhere. Richard produced them from his pocket.

"He's a wonderful salesman; he's perfect for Mel," says Janis Murray. "But you know what? I don't think this guy will rest until he gets on that stage and sings."

"Let's be honest," Howard Stern said to Richard. "Don't you think the Cowsills are kind of over with?"

For you, Howard, maybe. For Richard, they are as happening as Guns N' Roses.

Richard went on Stern's show last June to stake his claim in the dysfunctional-family craze, that brand of revelation now stretching across the celebrity firmament, from Roseanne to LaToya. His father, he tells Howard, took out his anger on his children.

"Black eyes, fat lips, welts," he repeats, months later as he sits in his kitchen. He says he was pushed through doors and windows. "Three times a week we were smacked around. Just because you didn't say 'No, sir.' There were seven kids. There were plenty of beatings to go around." (Bud Cowsill, now retired and living on the Baja peninsula in Mexico, did not respond to a written request for an interview for this article. But in December, 1990, People magazine quoted him as saying: "I'm a harsh taskmaster. I wouldn't want me for a father.")

Jan Murray supports Richard's story. She says she witnessed many beatings, was afraid of Bud herself. "Backstage, it was a horror story," she says, adding she had witnessed "terrible" fights, like one at the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas in 1969.

The Cowsills were to go on before an audience that included Elvis Presley. Bud wanted the group to sing "Buddy Can You Spare a Dime?" but Bill, the oldest son, didn't. "Bud was, 'Oh, you think you're so smart?' " Murray recalls "Bud hit him. Bill hit him back. Bud had Bill around his neck. I was holding onto Barry and Susan, and trying to keep Barbara from fainting."

Then the Cowsills went on and Murray heard them singing the signature phrase from "The Rain, the Park and Other Things"

"We can make you hap-py ... happy ... happy ..."

The other Cowsills, mortified by Richard's recent airing of family grievances, have refused to comment on the assertions. In other articles in recent years, some of his brothers have alluded to difficulties with their father, but they never talked about physical abuse. He had "mellowed" in recent years, they said.

"It's an attention thing, his public thing," Bob says of Richard. "I can sympathize, but I am not empathetic, because I didn't go through that . . . It's been how many years? . . . I'm 42. I'm just dealing with my life. It's a negative diversion."

For two years, Bob says, he has been focusing on a comeback. The Core Four are trying to get a recording contract. These days, they play club dates in Los Angeles, to highly favorable notices and they were recently nominated for a local music award for Best Unsigned Band.

Richard had desperately wanted to be a part of the comeback, and the Core Four, he says, had led him to believe he would be. They talked on the phone, exchanged letters. Richard pulls out one of them. It's from Bob, dated May 22, 1990. "With all of us up there, we'll really blow them away," the letter says. ". . . I've even pictured all of us going up for Grammies . . ."

"They were talking 'you're part of the family.' This was a letter of acceptance into the family," Richard says.

Richard put them up when they came to New York. His wife fed them. She did their laundry. Slowly, however, Richard and Susan came to realize the group would not become the Core Five. At a gig in Rhode Island, Richard was backstage watching his brothers and sister. Afterwards, he did what came naturally. He began to pack up the equipment.

"Bob came up to me and said, "We don't want you to move the gear; it's really embarrassing [us]' " Richard says.

Bob will not discuss his relationship with his twin. "We're not crossing paths with Richard right now. I'm involved in a serious musical pursuit."

It's an involvement Richard still craved. And then he confronted reality on "The Joan Rivers Show."

Today he is thinking solo singing career. His manager, Jack Gordon - whose main client is his wife, LaToya Jackson - says he think Richard should go into acting. Movies? TV? Theater? "All of it," says Gordon. "I'm thinking he would be, like, good in country-western-pop," says Benny Harrison, a musician who works with LaToya and may become Richard's music director.

Does Richard Cowsill have a future in show business, or is he destined to sell split-levels on the South Shore? Richard has no doubt where he's going. "I promised my mom," he says, "that someday I'd be center stage."

He sounds as if he believes it. Forget that he knows the words to only one song, or that he has performed alone in public only once in his life, in a karaoke bar in Freeport. He is a Cowsill. And the place for a Cowsill proves he is a Cowsill is in the spotlight.

A few days ago, after the interviews for this story were finished and the pictures had been taken, Richard called. A lot. How's it going, he wanted to know. How would he be portrayed? Are you still doing the story? One afternoon, he called again, with a question he was dying to ask. So, of course, he did.

"Is the cover photo for the article, he said, "going to be of me or my brothers?"

|

|