Making a Roll Out of Rock

Thre's a gold mine in booming teen records but if you're over 35, just forget it

Folk-Song Family Tries for Gilt Hit Parade

September 10, 1967

Daily News

New York, New York

Myrna Stogel checks on fitting of rock 'n' roll outfit for one of the Cowsills, a folk group you'll hear from.

|

|

As he steps out of his air-conditioned limousine carrying a black attaché case, he is the picture of the brisk youthful executive. At the glassy entrance to the office building, he is saluted by a white field marshal’s uniform with a doorman inside it.

In the elevator, office girls recognize him, nudge each other and speculate about what matter of pith and moment might be in the attaché case.

He enters his suite, strides through the crowd in the reception room and steps into the deep-carpeted office that smells of rich leather and success.

The first sound to break the dignified stillness is the “pop-pop” as he opens the snaps of the black attaché case. He takes out a small flat disk and flashes for his secretary.

Moments later the quiet is fiercely shattered by a blast of rock ‘n’ roll sound, the secretary ushers in his first appointment, and it becomes clear that the clean-cut, youthful executive is not the boy wonder of either IBM, GM or any of the 3M’s.

People walk boldly into his inner office who wouldn’t get past the elevator starter at U. S. Steel or DuPont. They are members of the generation that discovered hair. It dangles to the shoulders droops to their eyebrows and grows wild along the jaws, and their costume offers peekaboo views of body fuzz down to the navel.

But the dapper executive greets each one cordially for they provide the raw materials for the assembly line he operates as efficiently as a computer. And many a high-powered exec with a blue chip corporation would gladly swap for his money potential. He is Leonard Stogel, manager of rock ‘n’ roll acts. He is one of the entrepreneurs whose operations center on the record business which is pushing the billion dollar class with teen disk making up 25% of it.

Stogel started with one record and one singer just two years ago. In that short spell, performers he has lined up have sold more than 15 million records, and his organization is just beginning to grow.

Last winter it became necessary for Leonard, whose only associate at the outset was his chic blonde wife, Myrna, to take a whole suite of offices for Leonard Stogel and Associates, Ltd., now the parent organization for six separate operations. These include a management firm, two record production companies, two publishing companies and Heroic Age, a public relations firm devoted exclusively to the acts represented by the Stogels.

Looking back, Leonard, a 32-year-old who thinks Wall Street says: “It’s unbelievable how we get away with it.”

He is referring to the fact that before they picked up a languishing singer known as Sam the Sham, neither he nor Myrna had any experience managing acts. They were green – but the field was fallow.

He came back from a 1965 trip to Memphis carrying a record by the obscure performer. Sam, as every 1967 teen-bopper knows, wears a well-groomed beard, turtleneck sweater and slacks and an air of supreme confidence.

It was that confidence that impressed Stogel as much as Sam’s singing of a ditty called “Wooly, Bully,” and convinced him to take a flyer at management. “He told me he was going to be a star – just like that – and he had such a magnetic personality that I believed him,” Leonard said the other day.

“I learned one thing wearing out my shoes on the sidewalks and the seat of my pants in reception rooms, and that is never to turn anyone away automatically because you don’t know him. There are a lot of people in this town who are sorry they didn’t listen to me and my Sam record. I don’t want to miss anything good, so we try to give anyone who comes to us a hearing,” Stogel said.

The “getting away with it” was deadly serious at the time for plenty of chutzpah was needed in the negotiation of record contracts for the Sam and other acts he was signing.

“We would be in a high-powered meeting, and suddenly somebody would ask me a question about options or percentages that I didn’t understand. I’d look thoughtful, and then I’d ask for a few minutes recess and excuse myself.

“Once I was out of that conference room, I'd head straight for a phone booth and make a fast call to find out what the guy was talking about.”

Sam had recorded “Wooly Bully” for MGM but the record was going no place until Stogel latched onto him.

“As little as I knew about the business, I had no doubt that just plain leg work would be necessary to get started,” says Stogel, “and so Sam and I hit the road, visiting disc jockeys all over the country with our little record and our sales pitch.”

When they sensed a breakthrough as key DJ’s started playing Sam’s song, Stogel returned to New York to organize his operation and his budding star continued to peddle the platter from town to town.

“Wooly Bully” eventually hit the million mark and Len and Myrna, using their midtown apartment as an office, were assailed by mop-haired rock ‘n’ rollers day and night. “As managers, we took full responsibility for the kids we signed, even to the point of giving them a place to sleep,” he says.

On the night of New York’s power blackout, 14 people, most of them hopeful singers in their teens, slept in the small apartment.

“After that, Myrna would open the door to take in the milk and there would be three guys with long hair waiting in the hall. We decided we needed an office.”

Managing the promising youthful performers, some of whom came from poverty-stricken homes, often included arranging support, schooling and medical attention for brothers, sisters or parents. The Stogels call the tune for their teen-age idols down to the last penny of spending money. The youngsters are allowed no personal checking accounts, and the fantastic fees they command are handled by an investment counselor associated with Stogel. He buys them stocks, insurance and real estate. In the fast turnover of rock ‘n’ roll, success can fly as quickly as it comes.

“To a 20-year-old, this beautiful ride is going to go on forever. A boy walked in the other day and said, ‘I want to buy a car. I can afford it.’ I had to tell him: ‘You’re not ready for it.’

|

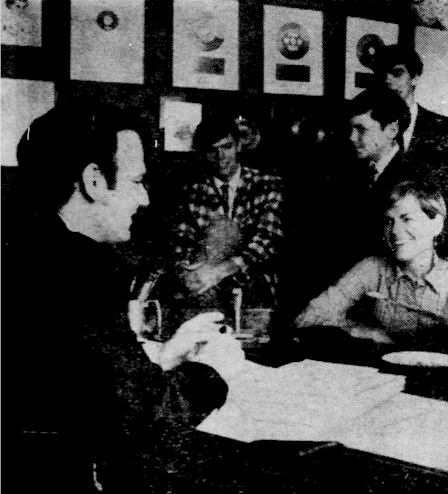

Leonard Stogel holds a counselling session with the Cowsills. The gold in rock takes a partnership - packager and talent.

|

Songwriter Artie Kornfield goes over an arrangement with the Cowsills. Folk-singing could bring them from plaids to riches.

|

|

“I won’t let them go the way of a top teen-age star of a few years ago. He’s working as a waiter, a few blocks from here. Blew a fortune, and his career is over.”

Movie potential is what Stogel keeps looking for in his clients, and in the case of Sam the Sham, it has already paid off. Stogel recently swung a three-year contact for him with MGM, under which the singer will be paid $500,000, guaranteed parts in two movies and not required to make a single record unless he – and his manager – wish to do so.

A percentage of those populating Stogel’s outer office fit the weirdo image of the business, but they are not destined to be his performers.

While he cannot control the way rock ‘n’ roll composers, arrangers, musicians or record producers not in his stable choose to wear their clothes or hair, he doesn’t follow the trend of “acts that cause a sensation through ugliness or shock.”

Such overnight flashes in the pan, he says, are not worth the investment his organization makes in a client’s career. This can run as high as $10,000 for musical instruments, amplification equipment, costumes, showcasing and publicity. Stogel’s office makes the performers over from head to toe.

One of the top Stogel stars, a 20-year-old named Keith who has all the teeners screaming, was taken off the road for 35 days recently to have his act restaged.

While Keith’s hair is a bit longer than some mothers or dads might approve, it is well-groomed, as are his clothing and manner, and he has the slim, photogenic looks of a movie actor.

Other heroes of the high school set under the Stogel wing are Tommy James and the Shondells, Napoleon XIV, the Royal Guardsmen, the Royalettes and Swinging’ Medallions.

At the moment, Stogel is working with a family of Rhode Island folk singers who he hopes will turn out to be the biggest Stogel stars of all.

Their name is Cowsill, and songwriter Artie Kornfeld, who spotted them in Newport, brought back an impressive story of their drawing power.

“I was up there to catch the Newport Folk Festival,” says Artie, “and I heard about this family that was singing at a little club. When I got there, that club was jammed – they drew 1,000 people that night, against 300 at the folk festival.”

The Cowsills a family of nine, of whom six are performers, will never make it in the hippy world. The boys wear jackets and ties, there isn’t a beard in the bunch, and when speaking to an adult they are likely to say strange things like “Yes, Sir,” instead of “Crazy baby.”

Their manager expects them to top the popularity of The Monkees. He has their first record, “The Rain, The Park, and Other Things,” set for release last week, and is giving them most full treatment.

When we were in the office at the contract signing, the Rhode Islanders were a happy, excited group. “Right after we finish here, you can go and look at your apartment,” their manager told them. “After that, downtown for clothing fittings.”

The family had good cause to be delighted. What was happening meant the fulfillment of the dream of their life-times. Bill Cowsill, an ex-Navy man, and his wife Barbara had raised their seven children with this one goal in view.

The years in Newport were not easy, but they were happy. “They lived in a big house, and the doors were never locked,” said a friend. “They had practically no furniture, and the stove was held together by a wire hanger, but anybody who came over was invited to dinner.”

The training of the four boys who do the performing, along with their mother and eight-year-old baby sister Susan, was evidenced when we went with them to an audition.

They accompany themselves on guitars, an organ and drums, and the drumming is done by Johnny, age 11.

Johnny, who is a better-looking Our Gang Alfalfa, gave out with a couple of “Yes Sirs,” when questioned, and then revealed that he had been studying the drums for three years.

Managers like the Stogels are not the only specialists who profit behind the scenes in the multi-million-dollar business that’s based on the weekly allowance dad shells out to junior and sis.

Besides the agents who book the rock ‘n’ rollers into clubs and theatres, there are those that produce the records. While the all-in-one Stogel organization includes Gregg Yale and Lauren Music, both production companies, specialists like the team of Koppelman and Rubin have grown enormously in the past year handling production alone for such clients as The Lovin’ Spoonful, Bobby Darrin, The Righteous Brothers and Gary Lewis and the Playboys.

Their success stories might make it appear that any shrewd businessman could reap a fast fortune on the teeners. But the experts warn that those who don’t know the business can wind up as broke as the get-rich-quick dreamers who joined in the Gold Rush a century ago.

Spotting a potential Gold Record, it seems, requires a combination of shrewdness and instinct as acute as that possessed by the one in a thousand who did strike it rich in the goldfields of California.

“There is no such thing as a trend,” said Don Rubin when asked if the secret of success in the record business isn’t simply the ability to tune in and then cash in on whatever the kids consider cool this season. Don and his partner, Charles Koppelman, both 27, have produced 23 records that hit the “Top 100” charts in two years, 11 of them making the platinum-plated Top Ten.

“You cannot predict what the kids will buy next,” he said. “People who think it’s only rock ‘n’ roll just haven’t been listening.”

He picked up a trade journal and ran down the list: “Here’s a back hills folk song at No.1, The Beatles at No. 2, a Frank Sinatra number marked as Upcoming, Barbra Streisand, Gary Lewis, Elvis Presley and Peter, Paul and Mary, who are folks all the way.”

The range in today’s teen taste, he pointed out, runs the full gamut from “Motown Sound” rhythm and blues through rock, folk and ballads of the Richard Rodgers variety.

The value of record producer or the manager, he said, is in picking the artist the kids will like, then finding him a writer who will tailor music to suit and showcase his talents.

To an adult who is hoarse from yelling, “Hey, you kids, turn down that noise!” the secret of success in the field just has to be put down as an unexplained phenomenon. Rubin, whose staff in New York and Los Angeles has a maximum age of 23 advises: “Don’t try to figure it out if you’re over 35.”

|

|