|

Susan Cowsill

In the late ’60s she was the little sister in the family act the Cowsills. Five years ago, she lost everything in Hurricane Katrina. These days, Susan Cowsill embraces the healing catharsis of music and the resilient spirit of New Orleans.

By Dan Forte

My Lord he’s done just what he said;

Let your light from the lighthouse shine on me.

Heal the sick and raise the dead;

Let your light from the lighthouse shine on me.

— Blind Willie Johnson, 1929

Though not an overtly religious statement, Lighthouse, the new CD by Susan Cowsill, is about death and grieving, as well as healing and hope and joy. She began writing its songs in 2005, after her New Orleans home and everything in it was lost to Hurricane Katrina. The storm also claimed brother Barry, one of five brothers she performed with in the Cowsills, ’60s pop-rock’s first true family band.

On this day, she’s in Austin, Texas, fitting in an interview over breakfast before going to record with Freedy Johnston and Jon Dee Graham. She talks about Lighthouse and what led up to it — inevitably encompassing her beginnings as a pre-adolescent rocker.

By a stroke of luck, Susan was in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when Katrina hit, recording with her longtime friend and ex-boyfriend, Dwight Twilley. She had recently married Russ Broussard, one of New Orleans’ standout percussionists. “We were going to go to Nashville for a gig the following week,” she details. “But my husband, who was still in New Orleans, had to evacuate.”

Their house took on six feet of water, and everything was lost — from Cowsills memorabilia and family pictures to equipment to just-purchased merchandise for the release of her first solo album, Just Believe It.

Eventually, she learned the fate of older brother Barry. “In 2005,” she recounts, “he had finally come to a place in his life where it was time for him to get his act together — for myriad reasons. He was scheduled on that Monday to take a plane to L.A., be picked up by my brother Bob, and he was going into a MusiCares rehab facility. The storm came, and I was out of town. His buddy said, ‘We gotta get outta here. I’m going to Florida. Let’s go.’ Barry was like, ‘I’ve got a ticket out of here for Monday. If we go to Florida, I’m looking at changing flights. And, in general, these things just come and go.’ Because they’d never had the big, big one.”

Barry stayed at his friend’s place in the warehouse district, and made it through the Monday storm OK. “He left me several phone messages that I didn’t get ’til that Thursday. Our cell phones didn’t work for days and days, but for some reason some landlines in NOLA were working, and he was going across the street to the pay phone. So he made it through the storm and said so, and then the water started rising and all hell broke loose. We were at [Timbuk 3’s] Pat McLaughlin’s house, and my phone started working, and I had all these messages. The last message from him, Thursday at 2:00 a.m., said, ‘I’ll call you in the morning,’ and I never heard from him again. He ended up drowned in the Mississippi.”

Ironically, on the day of Barry’s memorial, the family heard that brother Bill passed away in Canada following a lengthy illness.

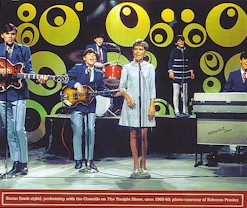

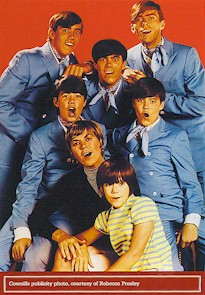

During a two-year period beginning in late 1967, Newport, Rhode Island’s Cowsills scored four Top 40 hits, with two of them (“The Rain, the Park and Other Things” and their version of “Hair,” from the Broadway musical) reaching #2 on Billboard’s singles chart.

They appeared on TV shows from Ed Sullivan to Johnny Carson to Mike Douglas and performed with hosts from Johnny Cash to Dean Martin, who dueted with Susan on “Shine On Harvest Moon.” They endorsed (what else?) milk — with such time-capsule ads as “Meditate on Milk” — and in October ’68 were the stars of their own comic book. (It featured fan mail and interviews with the band members, including this priceless exchange with Susan: “Do you have any message that you would like to tell everyone?” “Yes. My poodle’s name is Suba.”) A month later, they had their own NBC special, “A Family Thing,” featuring, among other things, Susan doing a soft-shoe with The Beverly Hillbillies’ Buddy Ebsen — in contrast to her usual bell-bottomed boogaloo.

The group’s original lineup consisted of brothers Bill, Bob, Barry and John. “That was before Mom and I joined,” Susan explains, “and it turned into this other thing. And then Paul joined. I joined in ’67, when I was eight. I know that for our Ed Sullivan Show [appearance], when ‘The Rain, The Park’ was peaking, I’d been in the band for two months. So I toured around that first record that I was not on. My first record with the Cowsills was We Can Fly. I’d been working on trying to get into that band forever. But I’d been the little sister. They were not thrilled with having their mother and sister in their band. Why would they be? They wanted to be the Stones or the Beatles, and certainly could have been. But they didn’t start out being somebody’s idea of pop or sweet — we’ll use the word bubblegum, which doesn’t apply to anybody, really. Before that, they were a really tight R&B/rock band. Once New York City got it, and that novelty of these brothers and their mother singing, it took on a whole other life force. It was certainly a part of who we were; it’s just not what [my brothers] had in mind. But it was clear that that was going to bring it to a place, perhaps, where once feet in, then you start to exert control over it. But that never happened for my brothers. It morphed and morphed, and the next thing you know we’re all dancing on an NBC special with matching grape Jell-O pants.”

If the brothers/sisters/parent lineup sounds familiar, it should. “We were slated to get our own TV show, which ended up being The Partridge Family. By the time they got to us, after developing for a couple of years, we were growing up real quick. Drugs, rock & roll — all that stuff — and time for family to separate. Also, they wanted a name actress to play my mom; we weren’t actors — just all these things.”

There is, of course, a long history of family ensembles in country music and bluegrass, but it’s hard to find a precedent in rock & roll. “No, I can comfortably say that we were the first family of pop rock & roll,” declares Susan. “We had the Osmond Brothers, but they weren’t rocked out yet; they were the guys on The Andy Williams Show. There was no one before us who was pop, modern, music of today, who had a family.”

To give some perspective, “The Rain, the Park and Other Things” entered the Billboard charts two years before 1969’s “I Want You Back” by the Jackson 5. The Osmonds’ metamorphosis, with “One Bad Apple,” didn’t come until early 1971.

In retrospect, rock historians have given the Cowsills’ their just due for their complex harmonies and arrangements. “Indian Lake,” from 1968, resembles the Beach Boys of the same period, for instance. And they’re often credited for being able to “make a bad song sound good” — with “Hair” usually cited. “That’s a good example to use, I think,” Susan laughs. “My brothers were and are very talented, legitimate musicians. Bill crested that scary zone of maybe genius — which can be a hindrance, too. To be able to hear something and find a unique way of returning it to you, and/or covering something spot on. We were also the best cover band, because we could sound exactly like who we were covering or make it our own and sound like the Cowsills. And that’s definitely what we did with ‘Hair.’

“I’m grateful that, when the book is finally closed, in the final analysis, we were and are a great band, with great songwriters and arrangements that were just beyond. And right as we speak, we’re the best band we’ve ever been. And that’s a beautiful thing. I mean, we got screwed financially. So at least artistically, if the proper accolades are made, I will feel a whole lot better — in honor of my brothers.”

|

|

Like so many groups of the day, inexperience cost them dearly in the pocketbook. Susan describes father/manager Bud Cowsill as “a charismatic guy and a go-getter — and a real asshole, too — but he didn’t know what he was doing. So once he got to New York, the Madison Avenue guys, as my brother Paul calls them, were twirling their mustaches, going, ‘No problem. Trust us.’”

Royalties and publishing were signed away in the process. “I don’t dwell on it, and never have, but it bothers me now mostly when I see my brothers, who are coming up on their sixties still working day jobs, and they shouldn’t be. I’ve lived my life, and I love my life. I live rent to rent and always have. I’m a musician; that’s the way it is. I’m fine. But there’s no way they shouldn’t be well off and playing out in the summers just for the fun of it.”

As with the Jacksons, the Osmonds, the Everly Brothers and others, the Cowsills had their own impossible-to-duplicate sibling harmonies. Asked when she discovered that ability, Susan responds, “Forever. Nobody had any training. All I know is my brothers could just sing, and my mother [Barbara] was a natural singer with no professional background. It’s completely DNA-oriented. There are six guys, and two of them got less of it. And they know it, and they’re OK with it. That being said, one of them, Paul, worked really hard to improve what pinch he had, and he’s great. My other brother, Richard, could have done the same thing, but for many reasons didn’t. And he had even less. That’s not a judgment thing; it’s a birth reality.”

Susan’s innate ability to harmonize eventually resulted in session work on 130-some albums with artists ranging from Nanci Griffith to Hootie & The Blowfish. “It wasn’t on purpose,” she says, “but when you’re known as a singer, people will call you to sing. From Carlene Carter and Howie [Epstein] from the Heartbreakers to Jules Shear — just the strangest people calling you up. The way I would enter every session was, ‘If you have harmony parts and know what they are, tell me what they are, and I will execute them. If you do not have harmony parts, and you don’t know what you want, I will show you a myriad of possibilities. If you do have harmony parts and want that, I’ll do that, but would you please just give me one track? I’ll go over it with what I’ve got, and you can have all of it, and use whatever you want — yours, mine, or both.’”

Her harmonizing extends to sister-in-law (and Bangles lead guitarist) Vicki Peterson, who is married to John Cowsill. In 1991, the two started sitting in with “all-star roots-pop” outfit the Continental Drifters, soon becoming full-fledged members. It was the Drifters who precipitated Susan’s move to New Orleans in 1992. “Also, I’d recently found out that I was pregnant [by Drifters multi-instrumentalist and then-husband Peter Holsapple], and I certainly didn’t want to raise a kid in L.A.”

The last official touring year of the Cowsills was 1972, but there have been various reunions since 1978, including an album, Global, in 1985. “When Barry and Bill passed away,” Susan says, “that definitely motivated a need to be together — which has gone until now. The current version is Bob, Paul and I. John plays drums for the Beach Boys, so Russ plays drums for the Cowsills. And we’re not done.” (In fact, a documentary is in the works.)

Of the various aggregations she performs with today, there is also, of course, Susan’s own band. “I didn’t start writing songs until I was 30,” she reveals. “I didn’t play guitar until my late twenties. I was just a singer, but I was absorbing it all. And 12 years with Dwight Twilley certainly planted something in there. But for me, searching for my girl singer/songwriter soul, it was all about Karla Bonoff. She was definitely my beacon of songwriting. Linda Ronstadt had been my big hero, and I knew that she’d done a couple of Karla’s songs, but then when I heard Karla doing Karla [on Bonoff’s self-titled 1977 album], that was a whole different reality. It spoke to me. I thought her voice was better than all those other girls’. There was a sense of honesty and vulnerability — not affected, just singing stories about she felt.”

Susan stepped out strongly on her own with the ill-timed Just Believe It.

“When I was with the Drifters, I had a few songs tucked away that were more pop-rock. Not only that, but I’d been avoiding going solo. I was offered a record deal with Columbia when I was 18, and I didn’t take it because I was in a band with my brothers. That would have been disloyal, in my opinion, at the time. I hadn’t lived a life enough to have a body of work that said, ‘This is who I am.’ So Just Believe It was, ‘OK, this is who I am — from Day One to here.’ It was a long time coming. I was of the mind that if I only make one record, I want it to be like Tapestry — important musically, and real. Then I could sit back and go, ‘I’m really satisfied with this. It’s who I am and what I am.’ I approached it very deliberately, and I was really thrilled with it. It came out a month after Katrina, and that says it all. There were a lot of plans for it, but then all hell broke loose. It was a secondary reality to me, in the biggest way — which is so sad. Russ and I toiled over it and saved the money, because it was important. Then Katrina came, and it was like, ‘What record?’”

Another ongoing creative outlet over the past five years has been her once-a-month Covered In Vinyl gigs in New Orleans, where Susan and her band (sometimes with special guests) pick a classic album and perform it start to finish. The two CIV albums released so far (with another in the wings) were recorded at Carrollton Station and feature material by Joni Mitchell, Fleetwood Mac, Aerosmith, Led Zeppelin, U2, the Beatles, Sly & the Family Stone, and others.

Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited was the subject of a recent CIV show, with diesel-country guitar master Bill Kirchen guesting. Susan details, “We met last summer on tour, and he said, ‘I heard about this thing you do. I want to come.’ We let him pick his own record. Bill is one of the sweetest, most precious 15-year-old spirits I’ve ever met.” (And, as if on cue, when asked about Susan, Kirchen exclaims, “She’s the bomb!”)

Springsteen’s Born To Run was especially fun, according to Susan: “I was stunned to see the joy and audience participation that he elicits. I opened my mouth with the words ‘Screen door slams, Mary’s dress waves,’ and then I could have been in another county, for all it mattered. The whole place just started singing at the top of their lungs. It was such a blast.”

More challenging albums to perform are “anything you take on that’s more than bass, drums and guitar; then you’ve definitely got yourself in a little bit of a pickle, outside that comfort zone. But part of my new band includes these kids — they’re 22 and 25 — the Craft brothers, Sam and Jack. They play cello, violin, fiddle, mando, piano, guitar; they’re all-purpose musical geniuses. So when I take on something like Sgt. Pepper’s or Abbey Road, we have all the sounds, one way or another. We’re not a tribute band, and a lot of times I’ll mix it up and change a song. The audience has to sit through an original set first, and then we do the vinyl. And it’s a really good muscle to exercise in one’s brain, to process all that music. You can’t help but be affected by it, cellularly, in your own music, because you’ve got this muse coming into your body every day. So maybe it makes me a better songwriter — I don’t know.”

Contrasting Just Believe It and her new CD, Susan offers, “Lighthouse, truly to me, is a much more realistic, now-time journey. Just Believe It was a long, long journey — a culmination of lots of thought and intention and care. Lighthouse is a real-time journey that took four years. I started writing Lighthouse songs right after the storm. But due to the nature of the trauma, I could not form thoughts and sentences, let alone complete songs. All of us were in a state of shock for at least a couple of years, then a state of trying to pull our lives back together. Make a record? I’m still trying to figure out where that damn can opener went that I used to have. I’m still looking for stuff and making sure my kids are OK and grieving the loss of my brothers. But all the while, all it takes is a napkin and a pen in a restaurant, if it comes to me. Sometime, about a year ago, we started feeling like we were recovering.

“Then, synchronistically — which is how everything comes at the most beautiful times, in my opinion — the Threadheads come,” she continues. “They’re a large group of people from all over the world who love New Orleans music and asked various artists, ‘What if we could get you the money to make the record?’ And, get this: It’s a nonprofit record company. You pay them back what they’ve donated — because they do it at a risk; nobody knows if a record’s going to sell or not — and then you match 10 percent of whatever monies you’ve borrowed and give it to the Musicians’ Clinic. Then you own your record, and the deal’s over.

|

“And it was time — to get over it, collect it up, put it in a box, tie up the bow, and let it go. That’s what this record is. It’s all the sorrow and all the joy and everything that came out of Katrina. And Lighthouse is very different to me, musically. I started hearing all kinds of crazy things, like strings and pianos and instruments I normally don’t hear when I’m writing. That was interesting and fun. I’ve said this before, but Lighthouse is truly this journey of a death. We have death; we have grieving time; we have a funeral. The funeral was the recording of the record and putting it to rest. My mission, on a therapeutic level, is to move through this Katrina thing. This next year or so, I’ll perform this record, and hopefully it will be stepping away from the more negative aspects of Katrina and bringing along the light of it — because there was plenty of it.”

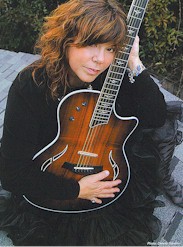

Joining Susan on Lighthouse are longtime friends Jackson Browne and session guitar ace Waddy Wachtel. The latter, one of Bill Cowsill’s best friends and composer of the group’s “On My Side,” plays on Barry’s “River Of Love,” which features brothers Bob, Paul and John, along with sister-in-law Vicki on harmonies and Susan playing Barry’s black archtop.

Susan plays rhythm guitar throughout her solo CDs and the CIV discs. But she says, “It was a hard road to get comfortable on an instrument and sing and play. It was a real challenge, but now I enjoy doing it. Certainly if I hadn’t started playing guitar, writing songs would be almost impossible.”

Her main guitars are two Taylors. She explains how her 814ce came into her hands: “At SXSW in Austin four years ago, I was telling Brent Grulke, who’s one of SX’s directors, how my Nanci Griffith Taylor — an amazing guitar that Peter had gotten for me — was stolen during a load-out. And Brent said, ‘Wait a minute,’ and gave me this guitar. It still had the sticker on it!”

Her T5-C1 was also a gift. “My brother Bob, who’s a big Taylor fan as well, gifted me that two Christmases ago,” she reminisces. “I had switched around [the pickup positions], and, to be honest, I had no flippin’ clue what I was doing until I got the DVD. So now it’s a whole new world for me, because those two guys [Taylor’s David Hosler and Brian Swerdfeger] were so cute on the video — and informative. I’ve got to say, with every ounce of affection, they gave guitar geeks rock-star status. The position second to the neck is the one I use for the Cowsills, and the one in the middle I use when Russ and I are playing a duo gig. Depending on what songs I’m playing with my band, I use the one closest to the neck or the second one. It always sounds great.”

Of the qualities she looks for in a guitar, she says, “I like bright with a little warmth. I don’t like dark and thuddy — not for my guitar. I want to hear a little Byrds jingle-jangle. I have a couple of songs I play in a DADGAD tuning, and I cannot talk and tune at the same time. It’s just not entertaining. So I tune the 814 to DADGAD, because they’re more acoustic-sounding songs.”

As for how her adopted hometown is doing today, she stresses, “Our local and federal governments have been shamefully remiss in assisting us in the way that they should. But on a community level, we’re doing awesome. We’ve taken care of a lot of business ourselves — as far as the stuff that would be otherwise taken care of by our representatives. We’re back to being in each other’s backyards; trees are blooming; grass is growing; and music is thriving again. Thriving in that everyone’s eating and bills are somewhat paid, but financially it’s not the same — as far as working at home goes. But we as a people are doing great.”

The journey of Lighthouse ends with “Crescent City Sneaux,” co-penned by Susan and Russ. The lyrics “I knew that I was going back to a place where I know who I am” float over breezy backing, before the rhythm seamlessly shifts to a rousing second-line groove as Susan references NOLA landmarks like Jackson Square and Café Du Monde, then quotes such Big Easy classics as “Iko Iko,” the Meters’ “They All Ask’d For You,” and “When The Saints Go Marching In,” finally rising to a crescendo of the beloved Super Bowl champions’ chant, “Who Dat say dey gonna beat dem Saints.” Proud, defiant, and cathartic, it’s been called “the best post-Katrina song” — an argument that’s hard to counter.

“We were among the first bands back — not living, but coming into town — and one of the first bands that played electric in town,” Susan recounts. “I played it at all of my shows that first month or so — pretty raw and tore up and broken up. I think it was a good cry-in-your-beer song for the town to embrace. I had no intention of writing a Katrina song. It was just something I wrote to keep myself sane and remind myself that everything was going to be okay.”

It’s perhaps too easy a metaphor, but, with it closing the program, the CD as a whole is like a New Orleans jazz funeral. “Yeah, man,” she exclaims; “I guess I’m a home girl! Seventeen years down there, and it’s now just actually in my body. There was so much love and compassion and community that came out of this, and I hope that is on the record as well. I cannot tell you how many wonderful gifts I received, emotionally and spiritually and universally, from this event happening, and I would not change a thing, for my own personal life. I take it as it comes, and every single thing that’s happened has brought me to this table and this awesome chicken-fried steak.”

She smiles a smile that, to this day, is equal parts pre-teen who can’t wait to gobble up that last bite and 50-year-old mother who has learned how to savor such simple pleasures.

For more information on Susan and the Cowsills, visit www.susancowsill.com and Rebecca Presley’s exhaustive Cowsills fansite, bapresley.com/silverthreads.

|